Comments:"In 1897, a Bicycle Superhighway Was the Future of California Transit | Motherboard"

URL:http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/in-1897-a-bicycle-superhighway-was-the-future-of-california-transit

In 1897, a wealthy American businessman named Horace Dobbins began construction on a private, for-profit bicycle superhighway that would stretch from Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles. It may seem like a preposterous notion now—everyone knows Angelenos don't get out of their cars—but at the time, amidst the height of a pre-automobile worldwide cycling boom, the idea attracted the attention of some hugely powerful players. And it almost got built.

Dobbins was able to win the support of an ex-governor of California, who in turn strong-armed a nay-saying legislature to get the bike highway approved. It was officially dubbed the California Cycleway. Here's a Google Map of its intended route:

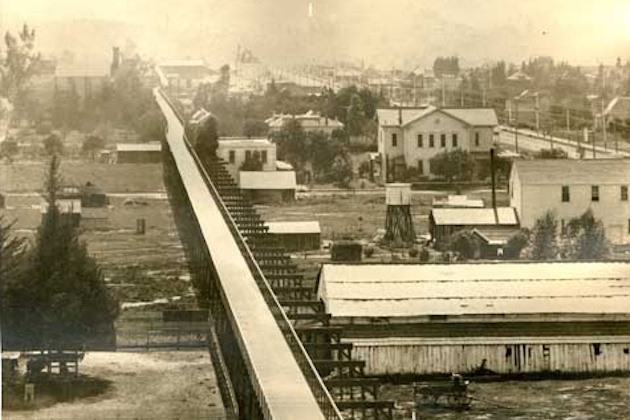

The first stretch of it, 1.25 miles across Pasadena, was in fact erected. The plan was to charge bicyclists 10¢ a pop for hopping on the bike-only highway one way, or 15¢ round trip. That's a savings of 50% if you make a day of it, folks.

The notion that anyone could profit off of such a venture—a bicycle toll road—seems insane now. But at the time, bicycling was a full-on fad. As in, something the rich, the hip, and the elite actually wanted to do. There were 30,000 cyclists in the Los Angeles region at the time, which was less populous then; it was home to 500,000 residents. A full 6% of Angelenos were cyclists.

The fascinating history of this cycleway—which, besides perhaps the toll scheme, is still a fantastic idea—was chronicled in this amazing 1901 article in Good Roads Magazine. The author was convinced that the cycleway was destined to be an integral part of the LA's transit future, as it could be adapted to service motorcyclists, too:

What a boon, therefore, is the new cycle-way to these beautiful California cities! It is thought that in five years time, industrial activity will be so quickened that the country will enjoy such prosperity as it has never known. Wheelmen increase and multiply every season. Motor cycles are fast coming in. The day is at hand when the motor-cyclist will be able to buy for a few cents enough compressed air to propel his machine for twenty miles at top speed ...The journalist went so far as to call the cycleway "one of the most noteworthy institutions in Southern California."

But alas, the bicycle craze was soon supplanted by the automobile craze, and the elites have never looked back. The cycleway was never completed, and was eventually abandoned. Part of the path cleared for the project was, somewhat ironically, turned into the Arroyo Seco Parkway.

That's Dobbins himself on the Cycleway, riding the machine that would be its demise.Bicycling has, of course, seen a resurgence in recent years. Bike-share programs are growing in popularity, and urban bike culture is obtaining a newfangled cache. But there are precious few places in America where actual infrastructure is devoted to cyclists—there are a few dedicated bike lanes in New York and Portland, but bicycling is still a Herculean feat in traffic-chocked, car-centric cities like L.A. A dedicated cycleway that would enable cyclists to escape the congested carnage there would be a godsend.

In Europe, cities like Copenhagen are embracing bike highways, and the percentage of bike commuters has skyrocketed. Which is great—well-regulated bike infrastructure eliminates congestion, improves a city's health, and, arguably, its happiness.

But we're still not so eager to follow suit here in the states—there's already talk of tearing up brand new bike lanes in New York. The 1897 Cycleway seems destined to remain a fine, fleeting dream.

Thanks to Nick Aster for the tip.